Crystal Quintero, Pfc. Sandoval; Amber Larson, Seven (eds.), Wisdom Quarterly; LA Times |

| Mexican-Americans and other Latinos wandering around the City of Angels (latimes.com) |

|

| Los Angeles' favorite soccer/futbol team, like its favorite cuisine, comes from Mexico (AP) |

|

| It's all about directly experiencing the Truth |

Q: If you were a "Mexican Buddhist," wouldn't you live in L.A.?

A: I guess that's true. I don't live in Latin America. I must be a Mexican-American Buddhist because I live in Los Angeles.

Buddhist temples here are very welcoming to people who speak Spanish or Spanglish. They try to be very accommodating to explain

the Dharma or offer meditation instruction.

|

| La Virgen de Guadalupe as Latin Guan Yin |

Beyond Chino Hills, far to the east near the massive Hindu

mandir which is larger than the Malibu forest

mandir, there is a large Thai Buddhist temple that tried to get a permit from the city to build a golden

stupa. The city said it was too big. So they cut it down to size and set it in the parking lot. That temple has a little guest house dedicated to Native Americans, who were once the locals before colonization and incorporation. When one asks the monks why it's there, they explain that it's out of reverence for the people who originally settled that land.

|

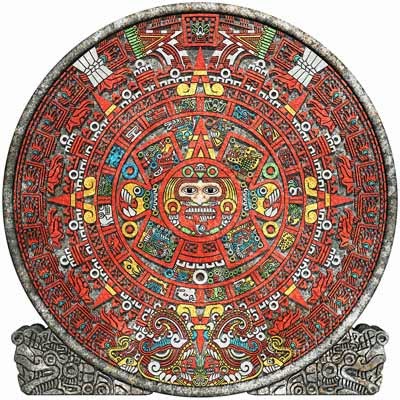

| Ancient Mexico in Mesoamerica was partially usurped to form the United States. Mesoamerica included North and Central America, including California, where the people remember the Mayan, Aztec, Toltec, and Olmec empires (wiki) |

|

| Reality check: El Pueblo de L.A. |

Going West (Hsi Lai) temple-complex in Hacienda Heights on the border with Orange County is very welcoming, too. They are a Taiwanese Mahayana missionary movement, so one expects it. One does not expect to be so warmly treated in about 100 much smaller temples that dot Latin neighborhoods all over L.A. County.

Q: And what Dharma message do you like best?

A: The message of independent thinking.

The Dharma is not about faith or priestly authority. It is about

free inquiry and a

sangha, a

community, that includes the people who practice the Path.

The Kalama Sutra tells us so, as do so many teachings of the Buddha.

Like the original

Protestant movement opposing corrupt Catholic institutions, Buddhism says we don't need an intermediary between us and the Truth, us and reality, us and enlightenment (seeing things as they really are), seeing the end-of-suffering (

nirvana).

We don't need idols, Gods, or heroes. They're all well and good. What we

need is

practice and

insight. And that's up to us. No one gets anywhere without help, but no one can help us so much that they are doing it for us. No one can do it for us. I think

Mexican-Americans can really relate to this. Maybe all Americans in our diversity can, like disaffected Presbyterians and languishing Lutherans [Editor:

Like my dad, you mean?] What did people want but a direct experience of sacred knowledge, liberating

enlightenment, of the divine, of the

entheogenic (

godhood-within) experience.

Speaking of diversity, before there was America there was Mexico. And Mexico was the place for diversity. It still is! The

Los Angeles Times recently (hardcopy June 13, online June 12, 2014) had a front page story titled "Mestizo Nation: Mexican DNA reveals a staggering range of diversity"!

Mestizo means "mixed" (

miscegenation, which was

illegal in the U.S. until the 1950s, but

has been and

is now one of the most popular things Anglos and Latinos do, like

Sofia Vergara and "

Al Bundy" on

Modern Family as the new

Lucy and her Hispanic hubby).

|

| Afghan, Chinese Buddhist missionaries to Cali |

"Mexico," it seems, gets its name from one Indian tribe, the

Mexica or

Mēxihcatls, who were Aztecs.

Mexicans again became

the majority group in sunny California in 2013, but now we're Mexican-Americans, and many of us are interested in Buddhism. After all, what few know is that Buddhism arrived in Mexico and California LONG before Europeans, Columbus, or Christianity.

Writers, artists, and historians have long pondered what it means to be Mexican. Now science has offered its answer, and it could change how medicine uses racial and ethnic categories to assess disease risk, testing, and treatment.

+fixed.jpg)