Amber Larson (ed.), Wisdom Quarterly; Maurice O'C. Walshe, (Migajalena Sutta, SN 35.63)

|

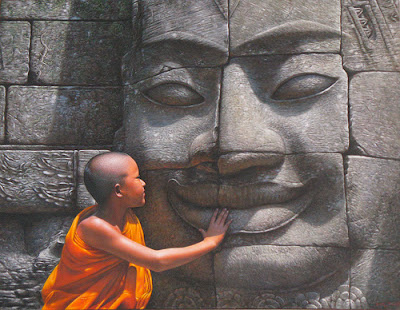

| Forest meditation under an umbrella-mosquito net, a Thai crot (withfriendship.com) |

|

| The Buddha with avian fighting naga (Sharko333/flickr) |

"There are, Migajala, objects cognizable by the [sensitive tissue in the] eye -- attractive, pleasing, endearing, agreeable, enticing, lust-inspiring.

"And if a meditator relishes them, welcomes them, persists in clinging to them -- then due to this relishing, welcoming, and persistent clinging, delight arises. And from delight infatuation arises.

"Infatuation brings bondage, and a meditator who is trapped in the bondage of delight is called 'one who dwells with another.'

"There are sounds cognizable by [the sensitive tissue in] the ear... fragrances cognizable by [the sensitive tissue in] the nose... tastes cognizable by the tongue... sensations cognizable by the body... phenomena cognizable by the heart/mind... and a meditator who is trapped in the bondage of delight is called 'one who dwells with another.'

"And a meditator so dwelling, Migajala, even though one may frequent jungle glades and remote forest-dwellings -- free from noise, [in sweet solitude] with little disturbance, far from the madding crowd, undisturbed by others, well fitted for seclusion [of mind and body] -- still one is termed 'one who dwells with another.'

"Why is this? Craving is the other one has not left behind, and therefore one is called 'one who dwells with another.'

"But, Migajala, there are objects cognizable by the eye...

"Without infatuation, no bondage is generated. And the meditator who is freed from the bondage of delight is called 'one who dwells apart [i.e., dwelling free of attachment, without craving].'

"And a meditator so dwelling, Migajala, even though one may live near a place crowded with monastics, lay-followers, rulers and royal ministers, and the followers of other spiritual teachers -- still one is termed 'one who dwells apart [free of attachment, without craving].'

"Why is this so? Craving is the other one has left behind. And therefore one is called one who dwells apart [free of attachment, without craving]."

"Why is this? Craving is the other one has not left behind, and therefore one is called 'one who dwells with another.'

"But, Migajala, there are objects cognizable by the eye...

- ear...

- nose...

- tongue...

- body...

"Without infatuation, no bondage is generated. And the meditator who is freed from the bondage of delight is called 'one who dwells apart [i.e., dwelling free of attachment, without craving].'

|

| The madding crowd (triggerandfreewheel.com) |

"Why is this so? Craving is the other one has left behind. And therefore one is called one who dwells apart [free of attachment, without craving]."